I saw it before he did. About five metres deeper, the size of an adult wombat. Dark, menacing, malevolent face fixed on us in a smouldering scowl. Before I could alert Andrea in a black and yellow bared-teeth blur it burst forth hurtling towards his head. It shot past his left ear then u-turned around his neck, torpedoed back to its original position, resumed its livid glare. Round 2. Andrea thrust his metre-long free diving fins forward and kicked but it didn’t flinch, ramming them then circling back in a fearless flurry of fins and swollen lips. Titan triggerfish: the pit bull terriers of the sea! I was bloody glad it went for him and not me. After three more charges it finally backed off and we were able to escape. The first dive of my Advanced Diver course was off to a cracking start.

The day before as we were zipping back to the Cakrawala Biru after our final dive, wetsuits peeled to our hips, bare backs towards the sun, absorbed by those sublime moments of recalling all the wonders we’d seen while getting warm, Andrea said sotto voce to Sarhil, “And then we convince Julia to do her Advanced course…”. My left eyebrow shot up and I gave him a knowing half-grin. I needed no convincing. “Yep. I wanna do it. And I wanna extend another day.” If money weren’t an issue I would’ve extended a month, or signed up for a six-week Dive Master course on the spot.

The Advanced Adventure Diver course comprises a range of five practical dives depending on the location and a few theory sessions, and allows one to dive to thirty metres rather than the Open Water Diver’s limit of eighteen. I’d be doing a deep dive, a night dive, a drift dive, a marine ecology dive and a navigation dive. (I reckon learning how to fend off a titan triggerfish attack should be a course requirement.) After Andrea and I escaped the treacherous trigger we descended to ‘the classroom’–a sandy floor at thirty metres–for my deep dive exam. At this depth the potential for nitrogen narcosis sets in.

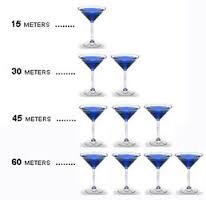

(A note for non-divers: The compressed air a diver breathes is a mix of nitrogen and oxygen. The deeper one dives and the longer one stays in the deep, the more nitrogen one inhales and accumulates in the blood. This is why as one ascends ‘safety stops’ are necessary–a series of pauses at decreasing depths for certain periods of time, depending on the depth and length of a dive. The decreased pressure enables the nitrogen in the bloodstream and body tissues to clear from the system, or ‘bubble out’. You’ve heard of ‘the bends’–decompression sickness is what happens when a diver ascends too quickly, and the nitrogen bubbles in their bloodstream and body tissues have not had time to clear. Nitrogen narcosis is caused by the nitrogen’s anesthetic effect, and at depths of thirty metres symptoms can include mild impairment when performing simple tasks, mildly impaired reasoning, and mild bravado, even euphoria. Normal recreation dives go to no more than forty metres, because beyond this the effects of nitrogen narcosis are far more severe–hallucinations, memory loss, unconsciousness.)

This is the first Google Image search result for ‘nitrogen narcosis diagram’. http://www.cps2011bioper7respiratory6.wikispaces.com

My Advanced Course deep dive exam was a nitrogen narcosis test. Andrea wrote a simple equation on his waterproof slate, ‘7 + 4 + 6’. Or was that 4 actually a 9? I scrawled ‘17’ on the slate and he shook his head. Aduh! I then drew an arrow to the ambiguous digit and scrawled ‘4 or 9?’ But by that stage I figured I’d failed so across the slate I scrawled an anarchy sign. We both had a good giggle and continued our chortling into the second stage of the test: Underwater Simon Says. Andrea did a series of movements which I had to mirror. Tugged his left ear, then right. Left hand on his forehead, right on his shoulder. Thumb on his nose, wiggled his fingers. I thought it was hilarious. Perhaps I was experiencing early symptoms of nitrogen narcosis which, Wiki tells me, is also known as ‘raptures of the deep’ and ‘the Martini effect’.

For my first ever night dive, off the island of Una Una in the Togean Archipelago in Sulawesi, there were only two torches between four, and so I shared with the Dive Master. This time we each had a spare.

“Who needs drugs when you have night diving in Komodo?” I wrote in my log book after one of the most psychedelic experiences of my life. Slowly descending into the inky darkness is both exhilarating and soothing, the only sounds one’s inhalations and bubble stream, the only light one’s torch beam, and the flashes of fellow divers’. During the day the reef is raucous with radio static, the rasps and scrapes and grinds and grates of a million ravenous mouths. At night most fish sleep in nooks and crannies, tail tips peeking from crevices and caves. At night the hunters reign, and what appears dormant during the day–hard and soft corals, urchins–at night comes alive to feed.

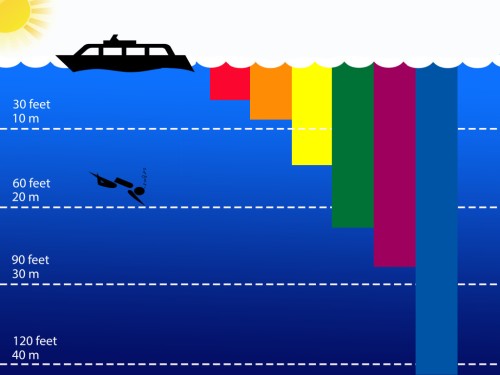

Spanish dancer, Hexabrachus sanguineus. http://www.stuffpoint.com

I once went to an ‘S’ themed dress up party as my favourite nudibranch the Spanish dancer, Hexabranchus sanguineus (literally ‘blood-coloured six gills’). Since I started diving I’d been desperate to see one. About ten minutes into the dive I did: a thirty centimetre beauty, its fuchsia skirts fluttering as it slowly slinked across the sandy floor. Spanish dancer! Spanish dancer! I was ecstatic. Red marine creatures are common at night–the Spanish dancer emerges at dusk and scarlet big-eyed soldierfish in the gloom are ubiquitous. As light travels through water it is absorbed and drained of its hues with red, the first in the colour spectrum, the first to fade. This is why few marine species have red in their visual palette, meaning red creatures are almost invisible to predators. At night divers see ‘true colour’, as the sole light source is one’s torch beam which is only filtered a few metres, and so most of its colour spectrum is retained.

The colour spectrum underwater. http://www.proscubadiver.net

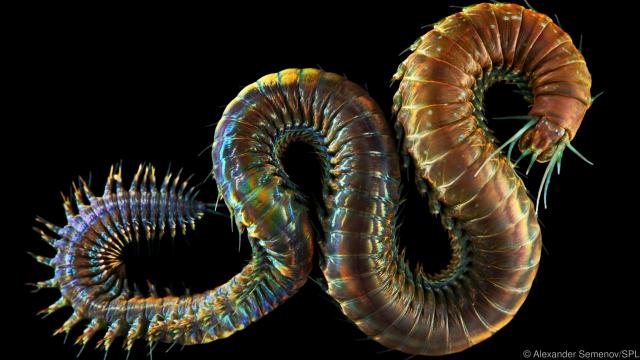

One’s senses, too, are more acute. During the day we’re surrounded by stimuli but at night we see only what lies beneath our light. And often what we glimpse momentarily in the day or disregard altogether, at night is completely transformed. The common sea urchin with its sinister spines is avoided for obvious reasons, but at night it becomes a Cycloptic plant in a mad scientist’s phantasmagorical greenhouse: its inverted stomach sack filtering plankton constantly swivels in perfect circles, an ever-watchful unblinking eye. Sweet little lilac soft coral, which earlier I’d admired like pretty blossoms swaying gently in a breeze, transform into mechanical tulips, petals opening and closing in unison with mechanical precision. I gawked at a metre-long violet worm as thick as a barnacle-encrusted anchor rope creeping out from beneath a coral bommie, lifted from George Lucas’ imagination. A velvety emerald nudi the length and width of a lavish croissant (which I’m yet to identify) perched like sunken treasure on a coral crag had me in raptures. As did a pearly white bobtail squid hovering in a cavelet next to a giant leopard cowrie twice its size. Little Julz the shell collector, the aspiring conchologist, squealed into her regulator with glee. ‘Twas watery heaven for me.

I reckon the George Lukas worm I saw was a ragworm (Nereis pelagica). This is a marine polychaete, a class of annelid (segmented) worm. Each segment has a pair of fleshy un-jointed limb-like appendages which aid in locomotion and act as external gills. http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150325-all-animal-life-in-35-photos

Does it get any cuter than a bobtail squid? http://www.otlibrary.com

For new divers the lionfish, with its sprawling spines and cream and umber stripes are indeed impressive, and warrant alerting one’s dive buddy for a look with the signal of interlocked, fluttering fingers. (For non-divers: underwater language is naturally all in the hands and many creatures have their own sign; for angelfish a halo is drawn around the head; a flat palm held vertically in the saggital plane of the head for shark; ‘air quotes’ mimic the nudibranch’s antennae, to name a few.) As lionfish are not uncommon, however, more seasoned divers would rarely feel compelled to alert their companion. But at night they glide slowly, stealthily through the black with foreboding spines fully unfurled, flaunting the cloak of an evil emperor, the regalia of war. The lionfish have learned well. They follow the torch beam to lock smaller fish in their sights, then in a blink swallow them whole. A diver can play god this way–holding the light on a fish to make it easy prey. With my light sweeping slowly I was startled a few times to find a lionfish stalking a mere foot from my right shoulder.

The next day’s first dive wasn’t far from the night dive site, Siaba Besar. Siaba Corner was like, I wrote in my log book, ‘a gorgeous morning stroll in golden light’. As the sun was yet to summit some of Pulau Siaba’s low peaks sections of its reef were still in shade, so certain fish were having a sleep in. I smirked at the cute little teal tail tips of red-toothed triggerfish peeking out from their beds. The next dive at Tatawa Besar was a drift dive (you allow the current to carry you along the reef) but it was mild, enabling frequent pauses for closer creature inspection. The entwined cream antennae of two giant lobsters emerged from a cave, their navy carapaces like hulking armor. A black tip reef shark patrolled the blue. A hairpin bend in the reef causing a confluence of currents created a popular feeding spot for a remarkable range of large fish (in my experience it’s rare to see large fish species intermingling; small yes, but seldom large). Many-spotted sweetlips and diagonal banded sweetlips schooled with spadefish–it was a tempat nongkrong, a happenin’ hangout spot! On the surface I mentioned this to Sarhil. “Iya mereka selalu ada di situ, senang nongkrong bersama.” They’re always there, they like hanging out together, he replied with a wink. It was a sparkling scene straight out of The Seahorse Café from my favourite picture book The Sign of the Seahorse by Graeme Base.

The Seahorse Cafe, a childhood dreamscape. http://www.graemebase.com/book/the-sign-of-the-seahorse/

That afternoon’s dive was the navigation dive for myself and fellow Advanced student Severin at Mawan, which is renowned as a manta playground. Almost immediately after descent three colossal winged creatures, one of them black, flew in slow motion towards us. We lay gently on the sand and settled in; the current was mild so tethering wasn’t required. The trio spiraled and looped a few metres away and was soon joined by an equally exuberant quartet, emerging from the blue like black swans in flight. We were in the centre of a giant oceanic manta ray acrobatics display, an indecipherable game of flair and grace.

It was so gripping I almost forgot Severin and I were supposed to complete a task: set the underwater compass’ twin red lines in the direction Andrea instructed us to swim, swivel the bezel so 0° is aligned with North, then for ten fin cycles swim to the cardinal points. With very mild current, easy. With seven giant mantas busting out some serious Cirque du Soleil, impossible. I couldn’t bear to tear my eyes away! Severin went first, but as Andrea assisted him the black manta barrel rolled a few feet in front of us. While the frolicking fish staged their spellbinding ballet we had to study a compass. I gesticulated melodramatically at it and then the mantas. Andrea, ever a mischievous mien behind his mask, pretended to throw it away. We spent seventy-three minutes with seven giant oceanic manta rays. On the surface I vowed to myself I’d work as a Dive Master one day.

Thank you Annik for the photos!

The penultimate dive at Tatawa Kecil on the following day, my last day diving in Komodo, punctured that promise. It was the day Andrea had warned me about, when the tidal currents were strongest due to the new moon’s perigee (its closest point to earth during its 28-day elliptical orbit). The day’s first dive at Police’s Point, in which we explored a cavernous cave-like overhang with torches, gave us some warning of their strength, but what we experienced at the second dive site I will never forget. I was paired with Severin while his girlfriend Annik was buddied with Andrea. A motionless two metre black tip reef shark was the first creature of note we encountered, lying on a rocky bed bordered by coral outcrops. But don’t sharks need to keep constantly moving in order to avoid drowning? Was it sick, perhaps dying? We carefully sought purchase behind a huge hemisphere of brain coral to observe it. I’d never seen a perfectly still shark before, the only signs of life its serried gills rippling faintly, like chimes in a feather breeze. I found the sight bitterly sad, so I beamed when with two tail flicks it scarpered across the reef, shattering the sharks can’t stop swimming myth.

We finned on with firm kicks, wary of the swiftly strengthening current. The reef was ablaze with thousands of anthias, violet, canary yellow and crimson, all skittering in the same direction. It was a frenzied marine megalopolis, a mega city whose every inhabitant was running terribly late. The fishes’ feverishness evoked those fraught final moments before a monsoonal downpour when everyone dashes for shelter sharing the same frantic expression. Bluefin trevally and green turtles flashed by in the blue. We began to be buffeted by surges necessitating strong finning, and I felt grateful for my many years of swimming training. Andrea instructed us to stay by his side and as close as possible to the reef. I focused resolutely on maintaining steady breathing as my heart rate accelerated rapidly. After all, I had nothing to fear. I completely trusted this man who, despite the velocity of the water, swam with his same seal-like ease and elegance. He motioned for us to clasp a cluster of hard coral and stay low. We clamped on with white knuckles, ensuring we all had equal grip while he hovered above, maintaining his position with seemingly effortless fin flicks. He was magic to watch.

Only a minute or two after we’d bolstered down with all our might the kaleidoscopic clouds of anthias darted 90° to the right. The reef fish flashed a warning that the current had changed direction, so it was crucial we did too. While being pummeled by the invisible force we clumsily maneuvered around the coral clump, trying our utmost to ensure everyone had equal purchase. With a fin flick Andrea rose slightly, then from his BCD withdrew an empty rolled up 1.25 litre plastic bottle. He unscrewed the cap, removed his regulator, blew into the bottle to inflate it, screwed the cap back on, returned his regulator. Clutching the neck with his right hand with his left he thrummed his pointer (a metal rod dive masters use to point to creatures or to bang on their tank to attract attention) across the bottle. The percussive pulse pricked the otoliths (the internal ‘ears’) of the bluefin trevally and their numbers multiplied immediately. Tuna and barracuda too now circled in predatory packs. White tip, black tip and grey sharks joined the spinning swarm, lured by the strange reverberating thrums. We were bolted down in the middle of a whirlpool while Andrea, Shark Whisperer, summoned the big fish. It was a piscatorial cyclone conjured by a merman with a metal rod and a plastic bottle. It was some party trick!

After fifteen minutes in the eye of the underwater storm, changing position every few minutes to face the current, Andrea motioned it was time to commence the ascent. He instructed Severin to grip onto the left side of his BCD, for Annik to grip onto the right and for me to grip onto hers. He then powered forth from coral cluster to coral cluster dragging us into the current, crawling across the reef and into the seething water like Spiderman until we reached the shallows. On the surface with wide wild eyes I flashed him a manic grin. He grinned back and said, ‘Now that was real diving.’

On 14 November this year it will be a proxigean spring tide. This occurs every one and half years, when the new or full moon is at its closest perigee (called proxigee), and coincides with a spring tide–when the earth, sun and moon are almost aligned. The effect on the tides is extreme. I hope those diving in Komodo that day stay safe and return to their boat with a smile as broad as mine.

Beyond the ken of mortal men, beneath the wind and waves,

There lies a land of shells and sand, of chasms crags and caves,

Where coral castles climb and soar, where swaying seaweeds grow,

And all around, without a sound, the ocean currents flow…

– Graeme Base, The Sign of the Seahorse

Recent Comments